Listen to any recording of your favorite flutist, and odds are one of the things that set them apart from other flutists is their use of vibrato.

Playing the flute with a natural-sounding vibrato is one of the most difficult things to master. For some flutists, vibrato comes naturally; for others, it’s an acquired skill.

But vibrato wasn’t always an essential part of our sound. It wasn’t until the 20th century that vibrato became widely used. In the 19th century, flutists used vibrato to highlight the peak of a phrase, according to Trevor Wye.1 The use of vibrato increased with the creation and adoption of the Boëhm flute.

It’s time to demystify the art of vibrato. Today, we’re diving into the essential element of flute playing that adds depth and emotion to your sound.

In this post, you’ll learn precisely what vibrato is, how it’s created in the body, and how to develop a naturally-sounding vibrato because no one wants to sound like a nanny goat when they play.

Get ready to level up your artistry because, let’s face it, your audience deserves nothing less.

Let’s dive in!

⬇️ Don’t forget to click here or down below to grab your FREE Step-by-Step Guide to Learning Flute Vibrato. ⬇️

What is Vibrato?

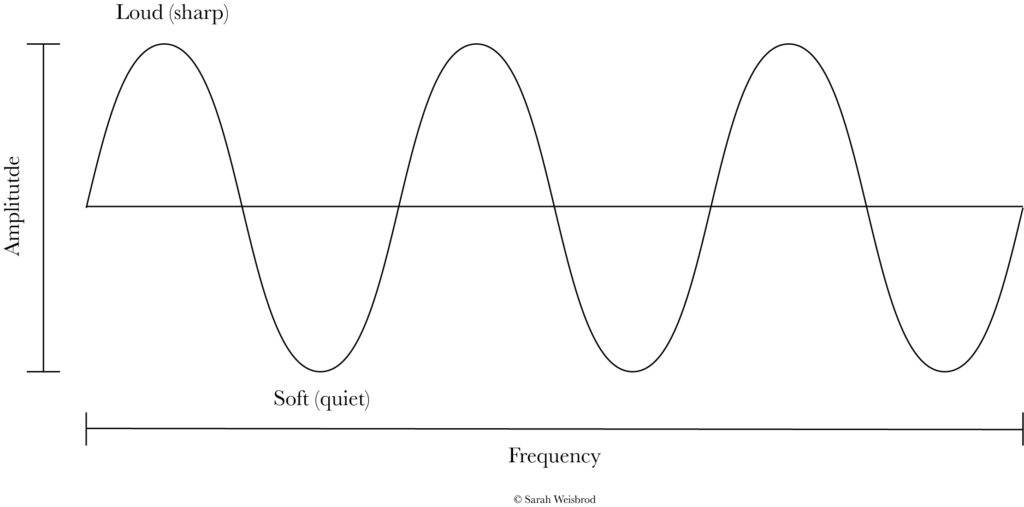

In order to understand how to physically produce vibrato on the flute, it’s necessary to first understand what constitutes vibrato. Simply put, vibrato is an undulation of pitch above and below the pitch center of the sounding note.

In his book on vibrato, Jochen Gärtner explains that vibrato “consists of periodic variations in the tone quality with regard to loudness, pitch, and tone color, which are produced by variations of the air pressure of the same frequency as the audible vibrato.”2

Moyse says that vibrato is “regular and simultaneous variations of the volume and of the pitch of a sound continued during its emission. These variations or undulations can be more or less rapid, more or less intense, and more or less pleasing. The quality of the vibrato depends on the quality of the tone, the technical facility, and especially the musical intelligence of the performer.”3

How Vibrato is Produced in the Body

There lies a great debate in the flute community about how exactly vibrato is produced.

Some flutists like Thomas Nyfenger believe vibrato is produced in the throat. On the other hand, Geoffrey Gilbert views vibrato as starting from the diaphragm and passing through the throat and larynx. And William Kincaid states that vibrato “is most probably produced by a combination of the delicate vibration of the throat and the elastic reinforcement of the diaphragm, acting together and sympathetically.”4

Three prominent flutists couldn’t come up with a consensus on vibrato!

However…there is one major issue with the idea of diaphragm vibrato: The diaphragm cannot pulsate to create vibrato.

Think about it. Try to exhale singing a note, and pulse your diaphragm. You can’t do it because it’s an involuntary muscle that moves based on other muscles.

To understand this, let’s take a look at how abdominal breathing works and explore the differences between diaphragm and throat vibrato.

The Diaphragm and Abdominal Breathing

When you inhale, downward pressure from the lungs filling with air causes the diaphragm to descend into the abdominal cavity. This causes your abdominal organs to move down and out. Some people refer to this as “abdominal breathing.”

When you exhale, the diaphragm relaxes and returns to its original position. The movement of your diaphragm upwards causes your abdominal organs to return to their original positions.

As you can see, the diaphragm moves as a result of the lungs inflating and deflating with air. It can’t control the rate at which air is expelled.

If the diaphragm can’t control vibrato, then what creates vibrato? Enter the larynx.

The Larynx

The larynx controls how much air passes through the pharynx by moving the vocal cords. To completely close off any airflow, the vocal cords come together entirely.

In laryngeal vibrato, the vocal cords never fully close as the cords move back and forth. This allows air to pass through the throat.

However, there’s one caveat with the larynx.

Using only the larynx and the vocal cords to produce vibrato results in the nanny goat vibrato. This happens when the vocal cords open and close too quickly. The French refer to it as Chevrotement.

Instead of eliminating the use of the larynx from participating in vibrato, Gärtner suggests determining how much laryngeal involvement is necessary for a natural vibrato.

This means the abdomen must play a role in supporting the air as it passes through the larynx.

Diaphragm/Abdominal and Laryngeal Vibrato

What people refer to as “diaphragm” vibrato is actually more like “thoraco-abdominal” vibrato. In this type of vibrato, the large muscle groups of the abdomen contract at low frequencies (speeds).

Laryngeal vibrato, on the other hand, consists of smaller muscles capable of “contract[ing] at much higher frequencies,” notes Gärtner.5

This means that a vibrato produced by only using the abdomen cannot contract and relax at a high enough frequency for typical flute vibrato speeds. Abdominal vibrato works by exerting pressure on the diaphragm, causing a fluctuation in the air.

Gärtner’s Study on Flute Vibrato

To determine exactly how flutists create vibrato, Gärtner performed a study.6 He gathered 12 flutists and had them perform three orchestral excerpts by Brahms, Bizet, and Debussy. He also had them play required notes with varying types of vibrato (larynx only, abdominal only, straight tone, etc.). The flutists were connected to electrodes at the larynx, diaphragm, and abdomen.

Gärtner found that the larynx is always active in the production of vibrato, even at low frequencies. Because of this, abdominal vibrato is always a mixed type – the amount of laryngeal involvement varies.

Higher vibrato frequencies were associated with the larynx, while lower frequencies originated from the abdomen.

To summarize Gärtner’s findings, what flutists often think of as diaphragmatic vibrato is vibrato from the abdominal muscles exerting pressure onto the diaphragm causing air movement.

The larynx actively participates in vibrato, but sole use of the larynx can result in a vibrato at too high a frequency. Conversely, relying solely on the abdomen results in a vibrato at too low a frequency. Therefore, flutists use a mix of both abdominal and laryngeal vibrato to obtain the desired vibrato frequency, even if they don’t actively think about flapping their vocal cords.

The Importance of Vibrato and When to Use It

Vibrato helps convey emotion, and it enhances musical expression. You can bring out a melodic line by altering your vibrato to show excitement or sadness. It can also help you highlight important notes in a phrase.

You should change your vibrato depending on the style of music you’re playing. For example, in the Baroque era, vibrato was a type of ornamentation. You should use it sparingly when performing music from that time period.

Vibrato isn’t a musical device that is always on at the same frequency and amplitude. It should vary depending on repertoire, style, and ensemble. When using vibrato, it should be within your sound and not expand past the tone’s center.

Your vibrato may even change within a phrase. For example, in the first study from Moyse’s 24 Petites études melodiques, you may start the first note with minimal vibrato, but by the peak of the etude, you will use a more intense vibrato to highlight the climactic moment.

Geoffrey Gilbert says that “vibrato—speed and width—should vary and match the volume or dynamic level.”7

Thomas Nyfenger notes that “vibrato is a color,” and you should be able to control the amplitude (depth of the vibrato) and vibrato speed. This frees you from the one-speed vibrato and gives you a huge range of vibrato potential from “clear, straight tone” to “impassioned, free-singing vibrato.”8

Flutists like Marcel Moyse advocated for a “vibrato that was part of the tone and expression of playing,” that it should be something natural.9

However, for some flutists, vibrato does not develop naturally, which is why it is essential to learn the mechanics of vibrato so that you can learn to have a free and natural vibrato.

How to Practice Vibrato

There are many ways to practice vibrato. The exercises below are the ones that I’ve found most helpful in reinforcing my vibrato.

While these exercises use a measured vibrato, I’m a firm believer that you should vary your vibrato speed and amplitude in your playing. Practicing measured vibrato will give you the necessary flexibility to play

You may find setting a metronome at ♩=60 to be helpful when practicing. But if that’s too fast, don’t be afraid to lower the tempo.

Practice “Hah”s

In order to have a natural vibrato, you first need to understand how the flute reacts to your air stream. Let’s do with by practicing breath pulses on “hah.”

Start on a B in the staff and do abdominal breath pulses on “hah,” without using the tongue to start the note. You should feel your abdominal muscles engage when exhaling. Your tongue should be relaxed on the bottom of your mouth.

Play one “hah” per breath, making sure each one is separated.

Even though vibrato doesn’t come from the diaphragm, it’s important to understand how the large abdominal muscles affect how air moves out of your lungs.

Try to crack up to a high partial to really feel how you can affect the sound.

Moyse would say, “When I do something in my body, the flute—it reacts.”

Slurred “Hah”s

Once you feel comfortable with your breath pulses on “hah,” start connecting them by slurring between each one. At this point, you’re still using your abdominal muscles only.

Think about each slurred “hah” as a big ocean wave. The peak of the wave/pitch happens when your abdominal muscles engage, and the low point comes as your muscles relax.

There should be an undulation in pitch and you may even hear a slight crescendo and decrescendo during the undulations.

Speeding Up the “Hah”s and Engaging the Larynx

In the following exercises, you’ll begin to increase the speed of your vibrato. When you do this, your abdominal muscles will do less work, and your larynx will engage to create faster vibrato.

Work on increasing the duration to eighth notes and eventually sixteenth notes. Finally, hold a long note and try to use vibrato.

Varying Vibrato Speeds

Practice with a metronome to vary vibrato speeds. See if you can pulse 5 times per note, 6 times per note, and 7 times per note.

Even though you want a natural-sounding vibrato, practicing measured vibrato gives you the technique necessary to vary your vibrato speed.

If you find that the note stops when you are trying to play with vibrato, that means your larynx is closing off the air stream.

If your vibrato starts to sound really fast, try relaxing your throat—you may be over-engaging your larynx.

Tips for Incorporating Vibrato Into Your Flute Playing

If you’re just starting off playing vibrato, try practicing slow scales or melodies to get a feel for how to play with vibrato. Then, try to vary your vibrato speed. Moyse’s Tone Development Through Interpretation provides various melodies to develop your flute vibrato.

Practice playing with different vibrato speeds (fast vs. slow) and amplitudes (wide vs. narrow). You can use a faster vibrato at the climatic moments of phrases and a more subtle vibrato when the music relaxes, like at the end of a phrase.

Different pieces and moments call for different types of vibrato. For example, the second movement of the Poulenc Sonata for Flute and Piano requires a different type of vibrato than in the build-up to the cadenza in the Martin Ballade.

Be sure you’re not making any extraneous movements to create vibrato, such as moving your flute or bobbing your head.

Now that you understand how vibrato works in the body and different ways to practice it, you’re ready to develop a natural-sounding vibrato.

If you’re new to vibrato, remember that it may take a while before you can easily vary your vibrato speed and amplitude. But, continuing to do these vibrato exercises will help you.

If you’re looking for a full written-out-for-you vibrato practice guide, I’ve got you covered. Look below for my Complete Guide to Flute Vibrato.

Much of this post was taken from my own academic research as part of my DMA. If you are interested in reading the full paper, please email me at hello@sarahweisbrod.com.

P.S. If you’re looking for a video tutorial, I highly recommend Emily Beynon’s YouTube video.

References

- Trevor Wye, “Book 4: Intonation & Vibrato” in Practice Books for the Flute: OmnibusEdition Books 1-5 (London: Novello Pub. Ltd., 1999).

- Jochen Gärtner, The Vibrato, with Particular Consideration Given to the Situation of the Flutist : Historical Development, New Physiological Discoveries, and Presentation of an Integrated Method of Instruction (Regensburg: G. Bosse, 1981).

- Marcel Moyse, The Flute and its Problems: Tone Development Through Interpretation for the Flute. (Tokyo: Muramatsu Gakki Hanbai Co., Ltd., 1973).

- Thomas Nyfenger, Music and the Flute (Guilford, CT: T. Nyefenger, 1986); Angeleita S. Flody, The Gilbert Legacy: Methods, Exercises, and Techniques for the Flutist (Cedar Falls, IA: Winzer Press, 1990); John C. Krell Kincaidiana: A Flute Player’s Notebook, 2nd ed (Santa Clarita, CA: National Flute Association, 1997).

- Gärtner, The Vibrato.

- Gärtner, The Vibrato.

- Floyd, Gilbert Legacy.

- Nyfenger, Music and the Flute.

- Trevor Wye, Marcel Moyse: An Extraordinary Man. Cedar Falls, IA: Winzer Press, 1993.

+ view the comments

Paragraph

for when you're ready—

🎯 1. 60-Minute Strategy Session

Big performance, audition, or jury on the horizon? In this one-off intensive, we audit your current practice, map out a data-driven plan, and troubleshoot the spots that keep falling apart under pressure—so you walk away with a clear roadmap, not more question marks. Book your Strategy Session →

🔥 2. Practice Strategy Intensives

Ever wonder why your practice works… until it doesn’t? Inside Practice Strategy Intensives, we audit your current practice, map out a data-driven plan, and troubleshoot the spots that keep falling apart under pressure—so you walk away with a clear, sustainable roadmap that holds up under performance pressure. Learn more about Practice Strategy Intensives →

📚 3. The Practice Code for Musicians

Want a complete practice system instead of piecing tips together from Instagram? My signature course blends strategy, mindset, and artistry to show you exactly how to practice for confident, consistent performances—on stage, in the studio, and at the stand. Join the waitlist here →

✉️ 4. Stay in the loop (and in the practice room).

Not ready for a full commitment yet? Get weekly practice tips, mindset tools, and behind-the-scenes stories straight to your inbox—plus first dibs on new offers. Join the newsletter →

You deserve to have a musical toolkit that allows you to thrive. I combine my expertise as a professional flutist and software developer to give you a methodical, science-backed approach to learning even the most difficult music efficiently and effectively.

I combine it with elements of the Alexander Technique and the art of musical storytelling and interpretation to help you eliminate anxiety and perform effortlessly and with ease. Your playing matters—you have something to say, and I'm here to help you say it.

featured

Feeling inspired to practice this summer but not sure what you should be doing? I’ve totally been there before. 🙌 When I was a college student, my teacher would send me on my way at the end of each year with my new recital repertoire in hand. It was exciting, but it was also somewhat […]

GETthe COMPLETE STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE to FLUTE VIBRATO

If you're ready to achieve a natural-sounding vibrato, this is the guide for you—featuring a 5-step tutorial walking you through learning flute vibrato from scratch.

Inside you'll learn:

- How find the reaction in your sound.

- How vibrato is produced in the body.

- Why you need a flexible vibrato.

- What types of vibrato to use in your repertoire.

- How to practice vibrato.

YES, I'll TAKE THAT DOWNLOAD

hot off the digital shelf

GETthe COMPLETE STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE to FLUTE VIBRATO

MORE TO EXPLORE

My 5 Favorite Venues in Southern Tennessee

Read on the Blog

You Don't Need *This* $$$ Wedding Vendor

Read on the Blog

Let’s fix what’s not working—so you can get back to playing, teaching, and creating with confidence.

learn about flute lessons

explore coaching options

get help with your tech stack

© Sarah Weisbrod 2026. All rights reserved.

Legal | Site Credit | Photography by AMG Photography