Being a musician takes a lot of hard work, perseverance, and dedication.

Spending hours alone practice can lead to practice overwhelm, frustration, and feelings of inadequacy as a musician.

But if you truly want to move your playing to the next level, you need to get over any limiting beliefs and fears you have about being a successful musician.

You need to spend your precious practice time focusing on key aspects of your playing to improve exponentially.

As the late French flutist Marcel Moyse says, “It’s a question of time, patience, and intelligent work.”

Plus, you need to know exactly what it takes to break through to the next tier. And that’s exactly what you’ll learn.

In this blog post, we’re discussing 11 things you need to implement to level up your playing and build better practice habits.

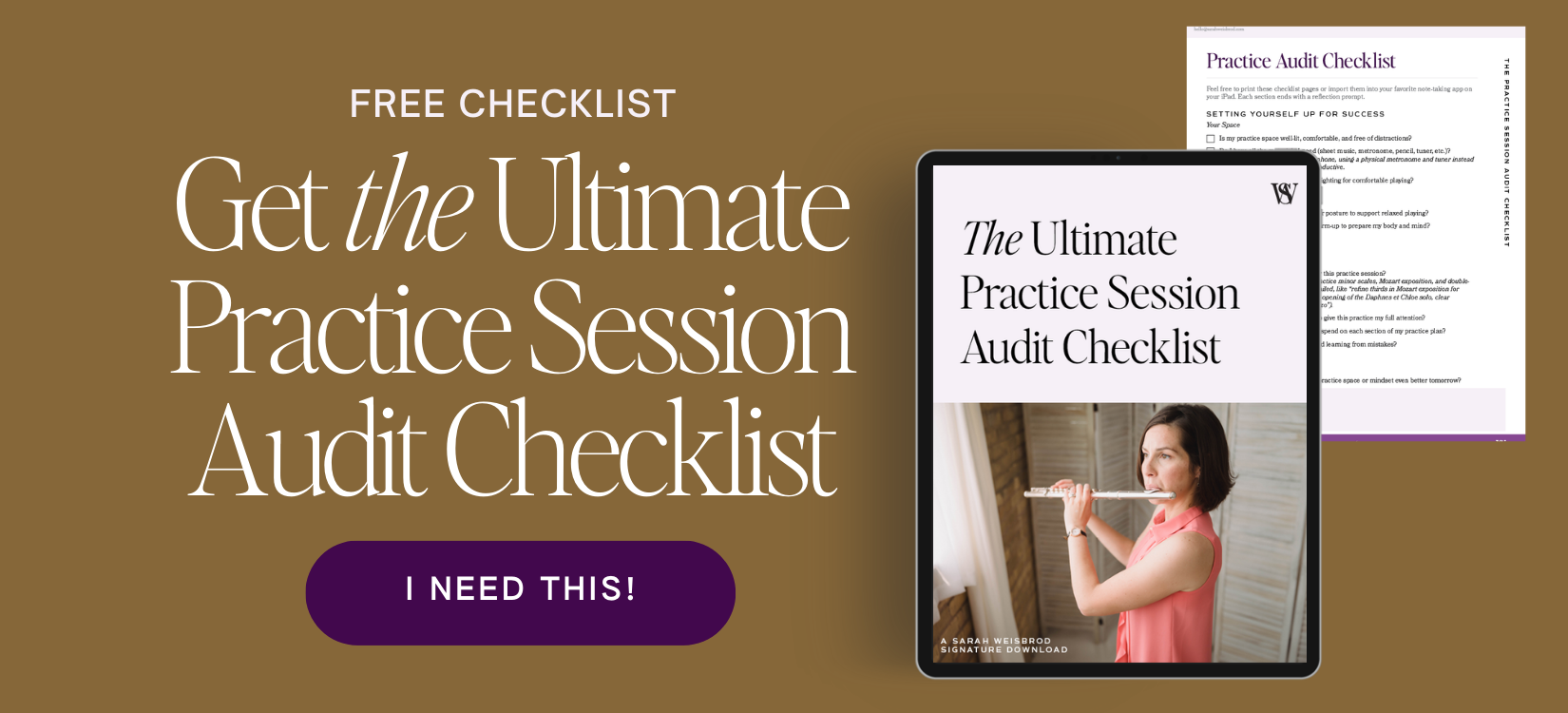

Want to make sure you’re not missing anything in your practice sessions? Download the Practice Audit Checklist. ⬇️⬇️⬇️

1. Understanding Pareto’s Principle

If you’re ready to become a better musician, you need to understand Pareto’s principle (the 80/20 rule) and how it applies to practice.

Basically, Pareto’s principle states that 80% of what you do comes from 20% of the work.

How does that apply to you as a musician and the growth you want to experience?

80% of the improvement you will make as a musician will come from 20% of what you practice.

Now, it can’t be just any 20% because if you always practice what you’re good at, you’ll never improve.

The 20% that will help you experience exponential growth comes from practicing what you’re not good at…which leads me to point #2.

2. Practice What You’re Not Good At

Make practicing what you’re not good at a priority. If you’re not sure what that is, ask yourself, “What is the thing I frequently avoid when practicing? What am I scared to practice?”

Most often, we think of procrastinating as an act of laziness, but really it’s avoidance. When you don’t practice what you’re not good at, you’re avoiding working on it.

And usually, avoidance comes from fear. It could be fear of success, “What if I finally get that orchestral excerpt right and win that job?” Or, “What if I can finally double-tongue? I’ll have to play more difficult rep.”

Having success on big and small levels can be scary, and one way our Stone Age brain protects us is by making us fear what we want. In 20,000 BC, that would protect us from being eaten by a saber-toothed tiger. But, in the present day, our Stone Age brain tries to protect us from failure.

You need to be like a buffalo. They run straight into a thunderstorm or snowstorm because they know it’s the fastest way through it.

Confront what you’re not good at head-on, and that tiny 20% will return big rewards.

And don’t worry if that 20% takes a while to learn.

In my college years, I always avoided practicing double-tonguing. Why? Because I wasn’t good at it. As a flutist, we have to do it a lot, and I sort of hacked my way through an undergrad. But I knew that if I truly wanted to grow and if I really wanted to get my terminal degree and elevate my playing, I would have to learn how to triple and double tongue. So, I made it a part of my daily practice.

3. Trust the Process

Trust that when you put in the work, you will see the growth. It may not be immediate, instantaneous growth—because you can’t hack your way towards becoming a better musician. But, you will grow.

Growing as a musician means getting better at something you’re not good at. It takes time—sometimes weeks, months, or even years.

When I was learning to play the Bach Chaconne from the violin partita BWV 1006, it took me 6 years to learn how to play 1 page that was all triple-tongued. 6 years!

Now, it was a piece that I practiced on and off, but my point is that learning to do something you can’t do takes a lot of patient work. It’s not like changing a lightbulb where the lightbulb wasn’t working, and all of a sudden it’s working.

Trust that the thing you’re learning may take time—whether that is a piece, a tricky passage, or a technical concept on your instrument.

And if you’re not sure where to even begin in this process of learning, this is something I teach inside the Practice Code for Musicians, but I also offer 1:1 coaching. So, if you’re thinking, “I wish I knew how to trust myself when I was practicing,” let’s talk.

4. Make Objective Observations

I’ve talked about this before but it’s so important. Changing the way I talked to myself in the practice room was one of the best changes I made in my approach to practice. It helped me learn music quickly and feel more confident when performing.

If you find yourself saying things like:

- “I can’t.”

- “This sucks.”

- “I suck.”

- “I’ll never win this audition.”

- “I’ll never be able to play this.”

You’re using subjective self-talk. And what you tell yourself, your subconscious saves to its long-term memory.

That means when you’re approaching a tricky spot in a piece or excerpt, your brain will believe that you can’t execute the passage. And that means you’re more likely to miss notes or have bad timing.

But there’s good news: you can change the way you talk to yourself—take the YOU out of it.

When you have an objective mindset, you don’t analyze your playing as a personal attack on you and your abilities. You are able to critique yourself without having any negative connotation on what you are or aren’t as a musician.

To implement objective observations into your practicing, ask yourself these questions after a run-through:

- Was I in tune or out of tune?

- Did I play with accurate rhythm?

- Did I maintain a steady tempo?

- Were there notes that were inconsistent or unstable?

Those types of questions will enable you to make faster progress with less likelihood of frustration. Plus, they’ll help you have the confidence you need to perform at your best.

5. Accept Failure as part of the Process

Don’t be afraid of failure. It happens, and it can happen on multiple levels.

It could be on a run-through of that passage that you’re working on. Maybe it doesn’t go as planned.

It could be an audition where you feel like you failed because the goal was to make it. And if you didn’t win the job, that meant you failed (oh, boy. ← That’s a whole blog post in and of itself).

But in actuality, you’re not failing. Failing is an opportunity to learn. Every failure—big or small—has its positives.

I see this a lot with my son. When he was learning to walk, he failed so many times. He probably failed thousands of times until he finally got it right.

And guess what? That will happen to you whether you’re learning a new concept, a passage, or you’re learning a new piece. It’s not going to be right from the get-go. (Side note: I don’t like the word perfect because nothing’s perfect.)

When you try something new, it’s not going to be right the first time. Know that it’s okay to fail and that you can learn from it.

When that passage doesn’t go as planned, ask yourself objectively (see #4 above), “What went right?” If you didn’t win an audition, ask yourself, “What did I do right? Where is there room for improvement?”

Find the positive in what you did. For example, if you’re working on learning a new concept, were you able to do that concept at a slightly faster tempo? The same thing applies to a passage you know. You may not be able to play it at tempo, but you can ask yourself, “Are the notes clear?”

Ask yourself what kind of progress you’re making. It’s a really good way to get a nice dopamine boost: “Yes, I’m making progress. I’m not quite where I wanna be, but I’m making progress.”

6. Believe in Yourself

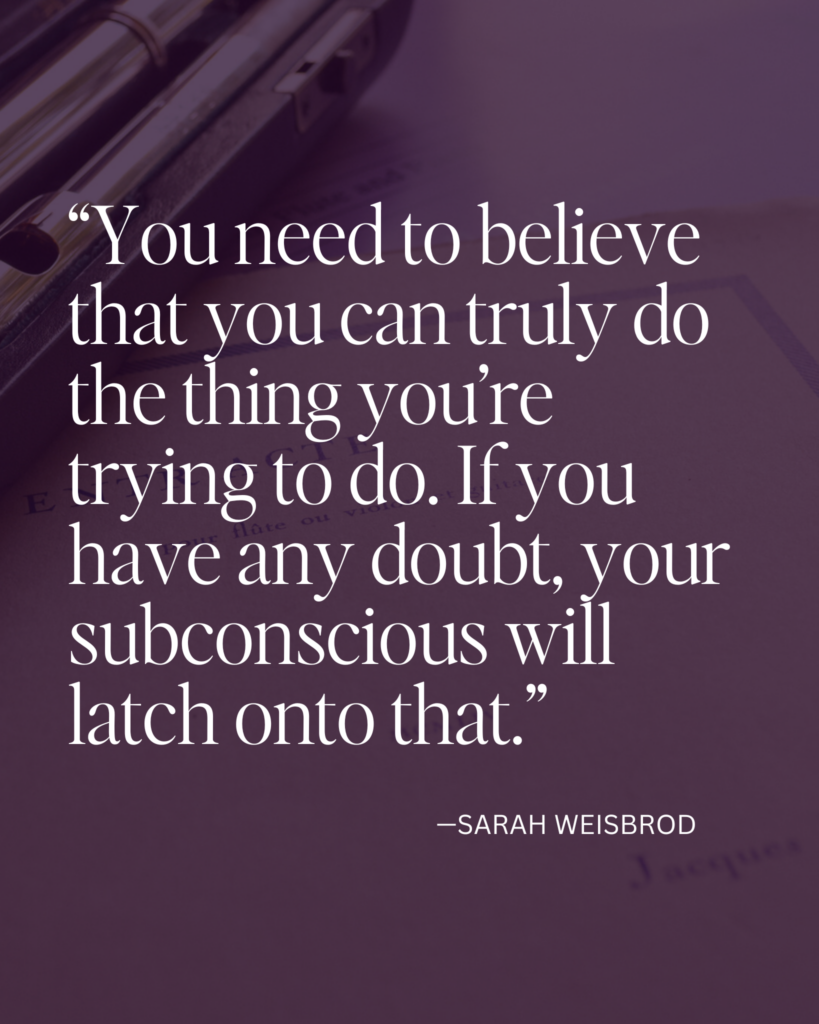

Our mind is a powerful thing. Sometimes no matter how well we know a piece, it’s our mind and our inner beliefs that shape whether or not we can fully execute at a high level.

You need to believe that you can truly do the thing you’re trying to do. Because if you have any doubt in your mind, your subconscious will latch onto that.

If you’re practicing a difficult passage and think any of the following:

- “Okay. Well, I guess that’s good enough.”

- “I hope I make it in the concert.”

- “I hope this goes well.”

Odds are, it’s not gonna go well. Yes, you need physical ability, but your mind is very powerful. And if your mind has any inkling of a doubt that you can’t do it, it’s not gonna let you execute that passage. It doesn’t matter if you have amazing technique.

Try changing any negative self-talk into positive affirmations:

- “I have the skills to execute this passage at the best of my abilities.”

- “I can play this backward and forward. I’ve got this!”

My favorite “hack” for limiting negative self-talk during a performance is to get excited for a passage instead of being afraid of it.

7. Practice Effectively

I could talk about this for hours. If you really want to level up your playing and overcome technical challenges, you need to use strategic, methodical, and effective practice strategies.

Simply repeating a passage over and over again and hoping you get it right—or repeating it until you get it right—won’t help you improve.

When you repeat things, you are reinforcing whatever you’re playing in your brain. And if the same notes that you repeat are the wrong ones, your brain will think those are the right ones. It doesn’t matter whether or not they’re correct.

It’s the same reason why when you go back to a piece after having not played it for a decade, you still make the same mistakes. You’re probably a much better musician, but you have ingrained the wrong notes into your brain. Your brain’s default execution plan is set, and it takes a while to fix it.

When you’re practicing, make sure that you are repeating for reinforcement or you are repeating to discover something. You could also repeat a passage to learn where exactly you’re messing up. If you’re unsure when and why something is unraveling, you need to repeat it to figure it out.

But, once you have the right notes and rhythm, you want to make sure that you’re repeating for reinforcement.

One helpful technique when it comes to difficult passages is to break down the passage. Find that part where it’s not going quite right and work out from there.

Use different methods like segmenting or memorizing. I’m a big fan of practicing things forward and backward. These are all things that I talk about in the Practice Code for Musicians.

8. Practice and Play Musically

You have to play musically, even when you’re playing something as simple as scales. Your playing needs to tell a story.

Here’s the thing: 9 times out of 10 in an audition, what sets the winner apart is the fact that they have a little something extra. Rhythm, tempo, and intonation. Those are all binary things that a committee can assess. Those are things they can use to weed out the people who move on.

But then you have to go beyond just playing the notes on the page. You have to figure out what the music is saying. How are the phrases constructed? Where is the peak of the phrase, and within a phrase, where are the mini peaks?

You have to create a musical narrative; you have to take the listener on a journey. Think of yourself as a magician. You have to show the audience the trick, so to speak, but you also can’t get emotionally involved in what you’re doing.

Lorna McGee, principal flutist of the Boston Symphony, says that “rhythm is character.” It’s one of the best ways to think about taking your music one step further. Use the rhythm to help you.

What is the character?

- Is it light or heavy?

- Is it somber?

- Is it filled with gratitude?

- Is it elation?

- Is it deep, dark, and mournful?

And the character doesn’t always stay the same throughout a piece. Even different sections can have different characters. So, don’t be afraid to use the rhythm to help you.

9. Record Your Playing

Recording your playing is the best way to really assess whether you’re making progress because the recorder doesn’t lie.

As you get better and listen to recordings of your practice sessions, you may feel like you’re getting worse. What’s actually happening is that you’re becoming more acutely aware of small discrepancies in your playing. I call this the Tolerance of Inexactitude. The better you get, the smaller it gets.

I see this all the time with my students. For example, they may be working on tone development and feel like they sound absolutely awful. But actually, their tone has improved immensely. They’re just much more acutely aware of what they like and don’t like in their tone, what they think is good or bad quality.

So record yourself. Make it a goal in every practice session to record at least five minutes of your session. Or, record a run-through so you can see where it’s at.

One of my favorite positive aspects of recording yourself is that it makes you a little nervous. It’s a 2-for-1 deal because you’re using recording to assess where you are and it gives you some performance practice.

If you have an upcoming audition or big performance, recording is a great way to work through your nerves sooner rather than later.

The more you record yourself, the more comfortable you get with the process.

10. Keep a Practice Journal

I can’t recommend this enough: Keep a journal of observations you make while practicing. And be sure to use positive self-talk.

Your journal doesn’t have to be anything formal. It doesn’t need to be a fancy bullet journal. It can literally just be a list of things you want to work on for next time or problem spots you want to cover.

You can also use your journal to brain-dump thoughts you have during practice. This allows you to stay 100% focused on what you’re doing. It keeps you from wondering about what you’re going to make for dinner or how you’re going to tackle a difficult passage in your Ravel. Write down those random thoughts. Get it on paper. Get it out of your mind so you can go back to what you’re doing, which is practicing.

11. Create Attainable Goals

Make your goals attainable. If you want to improve your double-tonguing, brainstorm what you want instead of saying, “I want to be better at double-tonguing,” which is somewhat vague.

What does getting better at double-tonguing mean? When do you get better? Set yourself a concrete goal.

For example, if your goal is to double-tongue at ♩=160. If you can only double-tongue at a ♩=60, now you’ve got a place to set your goal. So let’s say in one practice session you move up a couple of clicks; that’s great—you made progress. You achieved a small goal on the way to your bigger goal.

Then, all you need to do is set incremental goals until you finally reach your larger goal.

Wow, that was a lot! But now you have 11 ways to enhance your artistry and musicianship.

Let’s recap those 11 things:

- Understand Pareto’s Principle

- Practice What You’re Not Good At

- Trust the Process

- Make Objective Observations

- Accept Failure As Part of the Process

- Believe in Yourself

- Use Effective Practice Strategies

- Practice and Play Musically

- Record Yourself

- Keep a Practice Journal

- Set Attainable Goals

If you found this post helpful and want some help planning your practice sessions, check out this post.

⬇️⬇️⬇️ Don’t forget to grab your copy of the Practice Audit Checklist so you never miss a beat in your next practice session. ⬇️⬇️⬇️

+ view the comments

Paragraph

for when you're ready—

🎯 1. 60-Minute Strategy Session

Big performance, audition, or jury on the horizon? In this one-off intensive, we audit your current practice, map out a data-driven plan, and troubleshoot the spots that keep falling apart under pressure—so you walk away with a clear roadmap, not more question marks. Book your Strategy Session →

🔥 2. Practice Strategy Intensives

Ever wonder why your practice works… until it doesn’t? Inside Practice Strategy Intensives, we audit your current practice, map out a data-driven plan, and troubleshoot the spots that keep falling apart under pressure—so you walk away with a clear, sustainable roadmap that holds up under performance pressure. Learn more about Practice Strategy Intensives →

📚 3. The Practice Code for Musicians

Want a complete practice system instead of piecing tips together from Instagram? My signature course blends strategy, mindset, and artistry to show you exactly how to practice for confident, consistent performances—on stage, in the studio, and at the stand. Join the waitlist here →

✉️ 4. Stay in the loop (and in the practice room).

Not ready for a full commitment yet? Get weekly practice tips, mindset tools, and behind-the-scenes stories straight to your inbox—plus first dibs on new offers. Join the newsletter →

You deserve to have a musical toolkit that allows you to thrive. I combine my expertise as a professional flutist and software developer to give you a methodical, science-backed approach to learning even the most difficult music efficiently and effectively.

I combine it with elements of the Alexander Technique and the art of musical storytelling and interpretation to help you eliminate anxiety and perform effortlessly and with ease. Your playing matters—you have something to say, and I'm here to help you say it.

featured

Feeling inspired to practice this summer but not sure what you should be doing? I’ve totally been there before. 🙌 When I was a college student, my teacher would send me on my way at the end of each year with my new recital repertoire in hand. It was exciting, but it was also somewhat […]

GETthe COMPLETE STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE to FLUTE VIBRATO

If you're ready to achieve a natural-sounding vibrato, this is the guide for you—featuring a 5-step tutorial walking you through learning flute vibrato from scratch.

Inside you'll learn:

- How find the reaction in your sound.

- How vibrato is produced in the body.

- Why you need a flexible vibrato.

- What types of vibrato to use in your repertoire.

- How to practice vibrato.

YES, I'll TAKE THAT DOWNLOAD

hot off the digital shelf

GETthe COMPLETE STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE to FLUTE VIBRATO

MORE TO EXPLORE

My 5 Favorite Venues in Southern Tennessee

Read on the Blog

You Don't Need *This* $$$ Wedding Vendor

Read on the Blog

Let’s fix what’s not working—so you can get back to playing, teaching, and creating with confidence.

learn about flute lessons

explore coaching options

get help with your tech stack

© Sarah Weisbrod 2026. All rights reserved.

Legal | Site Credit | Photography by AMG Photography