I have a secret – I spent years practicing without a practice plan. I’m pretty sure I over-practiced in my undergraduate years because I didn’t set goals for each practice session. I was simply getting my hours in.

Since those undergrad years, I started planning more and more detailed practice sessions while incorporating my long term goals.

Having a practice plan makes it easier to react in high stress performance situations.

When I played basketball in high school, the coach would put up a practice schedule each day before practice started. Some drills we did daily, while others rotated in and out. I remember being so happy when the coach scheduled my favorite ones. And, at the same time, I dreaded the ones I didn’t like so much. It might not be a surprise that the drills I didn’t like focused on aspects of the game that were my weaknesses.

Each day the drills covered fast breaks, setting up offense, different types of defensive presses (full-court, half-court, zone, 1-3-1), free-throws, 3-2 drills, and probably more. We steadily built up the skills necessary for end-of-practice scrimmages. In fact, we often circled back to concepts covered earlier in practice so they weren’t forgotten. This also made it easier for us to react in game situations. Translate that into the music practice room: having a practice plan makes it easier to react in high stress performance situations.

But, you can’t just have a practice plan, you need an effective practice plan. It’s not fun. You have to practice what you’re not good at, and all too often it’s easy do anything but that. That’s why I’m going to show you how to create a practice plan. You’ll learn different types of organization so you can be sure you’re ready for any anxiety-inducing performance situation. Let’s dive in!

BTW, if you ever feel like you don’t know what to practice and just play whatever’s on your stand…

⬇️⬇️⬇️ Get your FREE copy of the Practice Audit Checklist. ⬇️⬇️⬇️

Step 1: Decide what to practice

This might sound obvious, but I can’t tell you how many times I’ve picked up my flute and started practicing, moving onto different things at my own leisure. When this happens, it’s easy to forget exactly why you’re practicing.

Before you even take your flute out of its case, decide what you’re going to practice. Ideally, your practice sessions should include the following:

- Tone – including tone development

- Technique – I like to work on articulation and technical coordination when I practice my scales. It makes them less boring. Plus, I’m working on several things at once.

- Etudes – Not all teachers assign etudes, if yours doesn’t, don’t worry. Spend some additional time on technique, tone development, or find some free etudes on IMSLP.

- Repertoire

- Score study is also practice, you’re practicing away from your instrument.

Step 2: Find specific items to practice within your generalized list

Now that you know some main elements to practice, it’s time to choose specific items within those sections to practice. This is especially important when practicing your repertoire. Playing your piece over and over again isn’t practice, it’s playing your piece over and over again.

To practice efficiently, you should find specific sections of your piece(s) to practice.

For example purposes, let’s say my repertoire is:

- Mozart – Concert in G Major

- J. S. Bach – E minor sonata

- Ibert Concerto – first movement

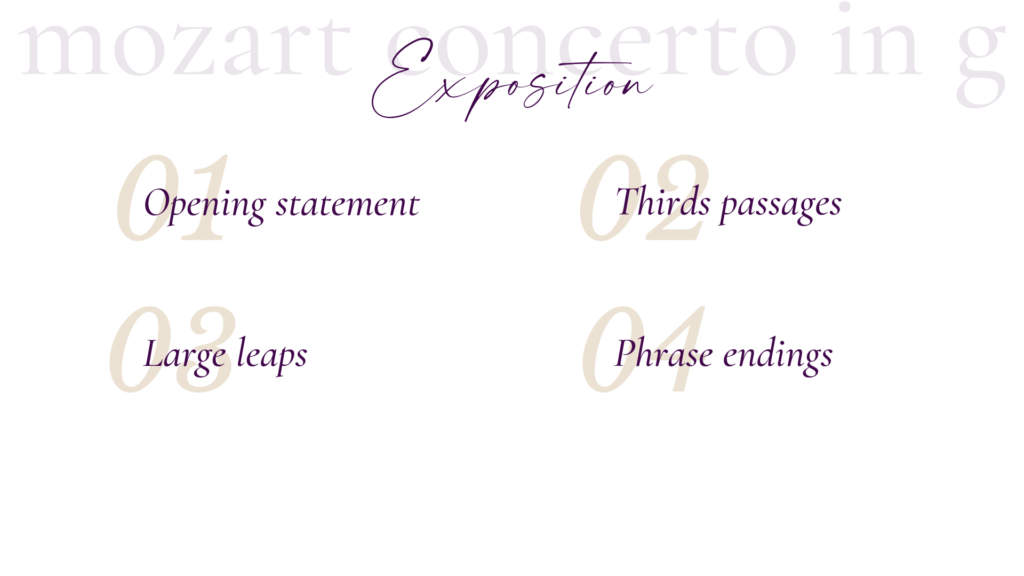

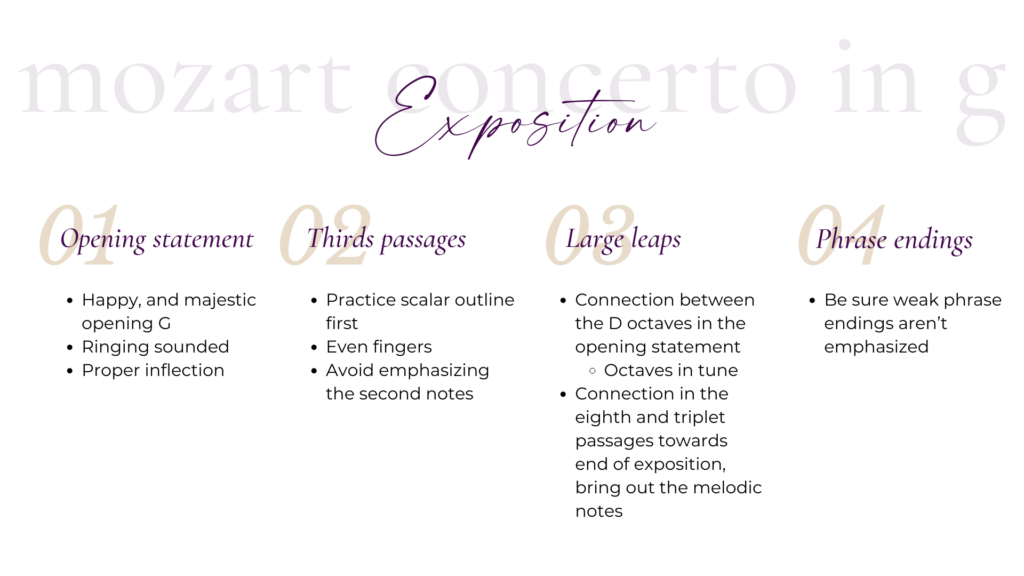

There’s no way one can practice all that repertoire in one sitting. For each piece, pick a movement and several sections that you want to address. If I’m working on the exposition of the first movement in the Mozart, the list of items I need to work on may look like this:

Step 3: Create goals within items in your list

Have you ever heard of SMART goals? The acronym stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-based.

You need to create goals within each item in your list so you know exactly what to work on. These are small short-term goals that, for now, focus on the SMAR part. Taking my exposition list from Mozart in G from above, and adding more goal-oriented detail, my list may now look like this:

Step 4: Determine the amount of time you have to practice

While this step sounds obvious, understanding what you need to accomplish and under what time constraints will help you develop a well-structured practice plan. Remember that you don’t have to practice all at once. If you are a music major and need to practice 3 hours, you could do 2 hours in the morning and an hour in the afternoon.

You’ll use your total amount of practice time for the session when it comes time to organize the items and goals from above.

Step 5: Determine when to take breaks

You need to take breaks while practicing.

Practicing for hours on end without a break can lead to muscle overuse resulting in possible injury as well as mental and physical fatigue. You may end up OVER practicing by not taking breaks.

I like to take small 5 minute breaks roughly every 30 to 45 minutes. I usually take my first break after long tones then again after scales/technique, then every 30 minutes thereafter. This is similar to the Pomodoro Technique that emphasizes bursts of concentration followed by a brief break. Every 60 to 90 minutes, I may take a slightly longer break. I find that break strategy works best for me, but everyone is different so it might take awhile before you figure out what kind of break works best for you.

Step 6: Create Your Practice Plan

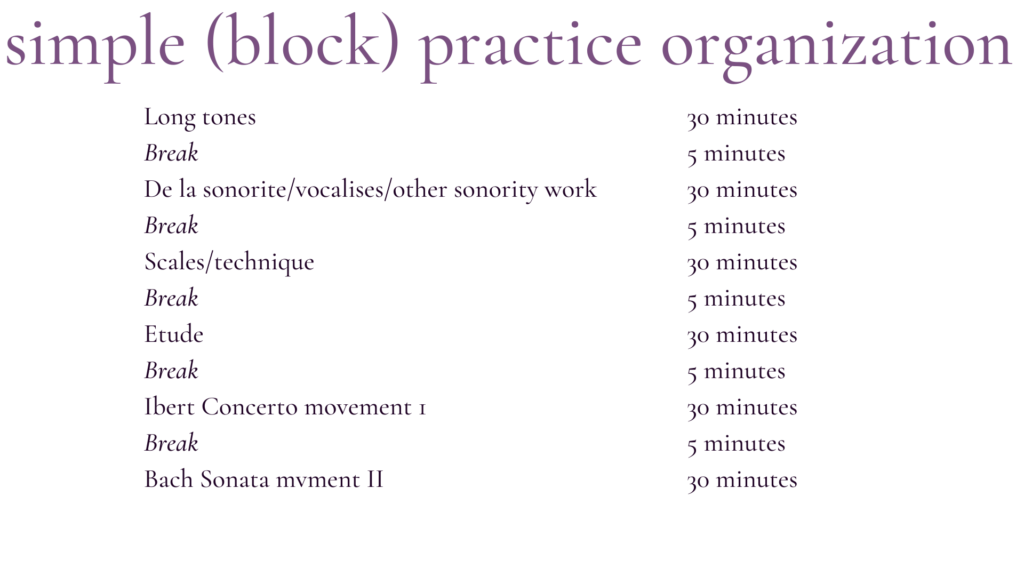

A very basic practice plan may look like this:

This looks like a very good practice schedule, but it has some limitations.

- This schedule is not very detailed. What happened to the work we did above? Where’s the Mozart stuff that was so carefully planned?

- Everything is done in a chunk. In this schedule, nothing is ever revisited so that the work is reinforced.

- The Bach and Ibert movements feature a lot of double tonguing. By the time I get to Bach, I may not be able to execute everything properly.

If this type of plan works for you, great. BUT… I think you can get better results if you create a plan that is more like the one below.

Let’s step it up a notch.

In a guest post on Noa Kageyama’s Bulletproof Musician, Dr. Christine Carter discusses different types of practicing. The practice schedule above is akin to block practicing where one element is worked on over and over again, but never revisited. This type of practice may be helpful if you are in the early stages of learning a piece where you need more time to digest the material.

A practice model I like, which both Dr. Carter and Andrew Bain – principal hornist of the LA Phil discuss, is a random or interleaved practice schedule. Instead of focusing on one thing repeatedly, interleaved practice involves circling back to concepts visited earlier. This is exactly like the basketball schedule from above when important elements reappeared throughout the schedule.

Let’s say I need to practice an etude, Mendelssohn Scherzo, Mozart G major exposition, Ibert concerto first movement, and Bach E minor movement II along with scales and long tones. Because Ibert I is so articulation intensive, I’m going to sub Bach E minor I for Bach E minor II so that my repertoire for the practice session isn’t solely focused on double-tonguing.

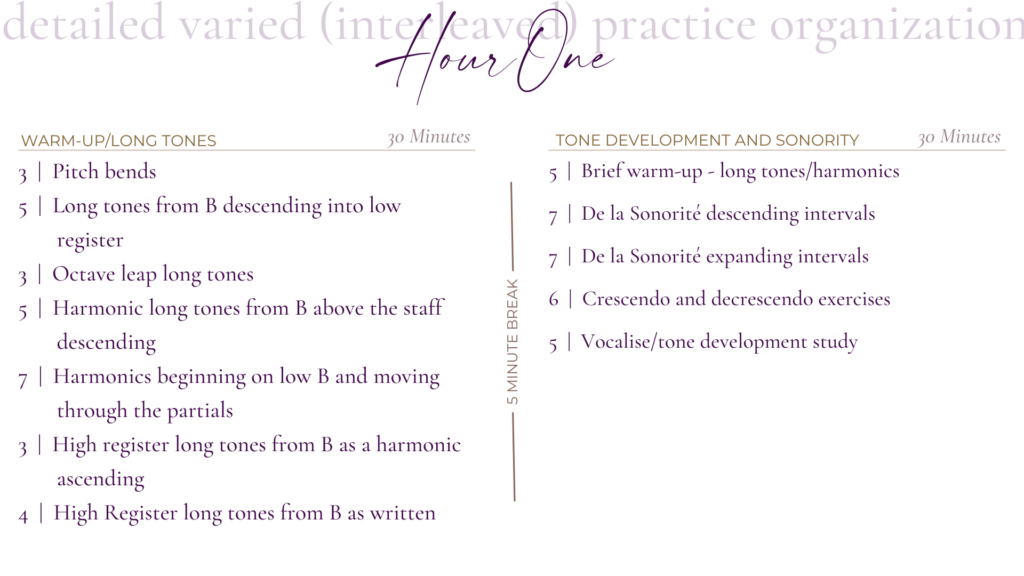

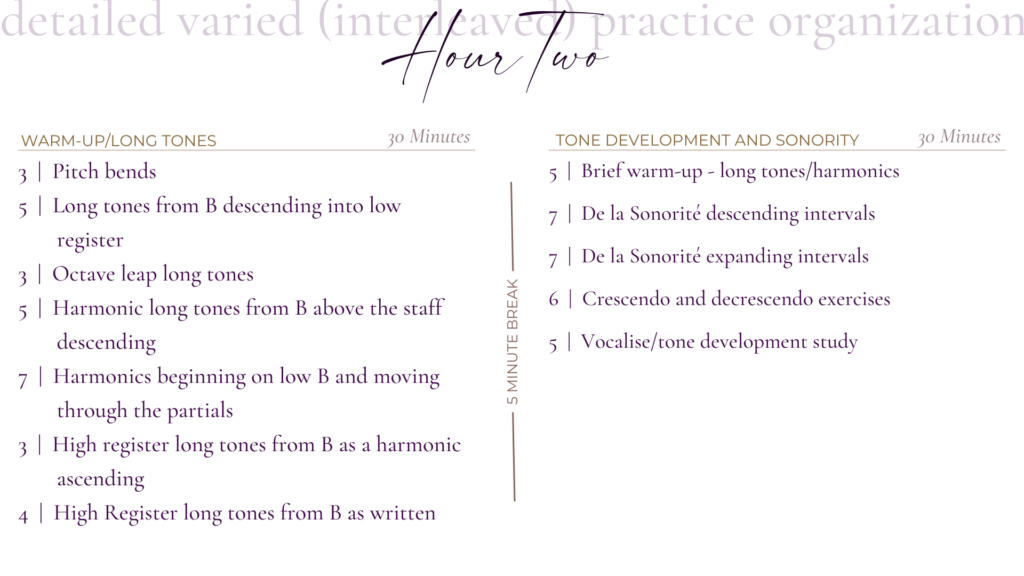

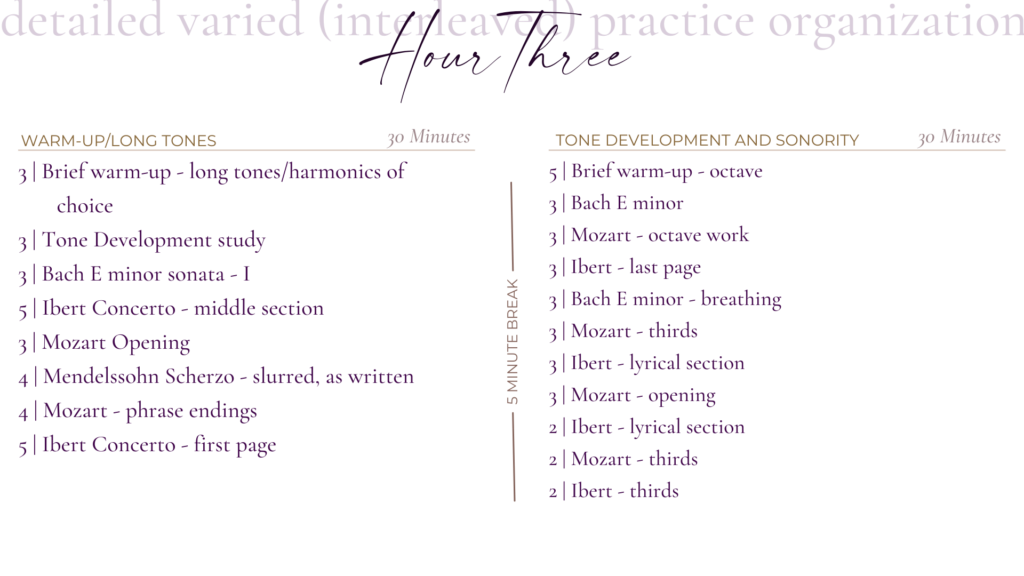

Using this schedule, the interleaved practice method, and a 3-hour practice block, I can create the following schedule:

If you look at my practice plan you’ll notice a couple things:

- The plan focuses on 3 pieces of repertoire.

- It incorporates my specific items from Step 2 above in my Mozart strategy.

- I circled back to previous material.

- The final 30 minutes has a lot of short bursts to ensure I was revisiting items.

- More than half my practice was spent on fundamentals so that working on my material would be easier.

How to Plan Your Practice Session

No, I don’t plan every session with detailed graphics, and you don’t have to either. A simple system will do.

I use a dot grid journal so I can create a customized plan for the day or week, depending on my schedule. You can use a paper journal, computer spreadsheet, or a list on your phone. Personally, I prefer a paper journal so that I’m not distracted by electronics when practicing. Do what works for you.

The Coda

Be kind

On bad tone days, you may need a longer warm-up. If you feel that may be the case, restructure your schedule with that in mind.

Find what works for you

Block and Interleaved practice structures have pros and cons. I like block when learning new repertoire and interleaved when I’m maintaining and closing in on a performance.

Now that you know how to create a practice plan for your practice session, it’s time for you to figure out which method works best for your learning style and situation. You could take more of a generalized block practice approach (which I sometimes like for my early stages of learning a piece) or you can take a varied/interleaved approach, where you circle back to pieces and practice in short chunks. Or you could incorporate both into your practice session.

Whichever you choose remember the following:

- Have clearly defined goals for each session

- Map out what exactly you want to practice

- Take frequent breaks

⬇️⬇️⬇️ Don’t forget to download your free practice session audit checklist so you can build the kind of performance confidence that doesn’t hinge on anyone else’s opinion—and start letting go of external validation in music once and for all. ⬇️⬇️⬇️

Sources:

Noa Kagayama – Bulletproof Musician

- 3 types of practice strategies

- Productivity in the practice room, with Dr. Christine Carter

Andrew Bain – Principal Horn LA Phil, Invested Musician

+ view the comments

Paragraph

Previous Post

Next Post

for when you're ready—

🎯 1. 60-Minute Strategy Session

Big performance, audition, or jury on the horizon? In this one-off intensive, we audit your current practice, map out a data-driven plan, and troubleshoot the spots that keep falling apart under pressure—so you walk away with a clear roadmap, not more question marks. Book your Strategy Session →

🔥 2. Practice Strategy Intensives

Ever wonder why your practice works… until it doesn’t? Inside Practice Strategy Intensives, we audit your current practice, map out a data-driven plan, and troubleshoot the spots that keep falling apart under pressure—so you walk away with a clear, sustainable roadmap that holds up under performance pressure. Learn more about Practice Strategy Intensives →

📚 3. The Practice Code for Musicians

Want a complete practice system instead of piecing tips together from Instagram? My signature course blends strategy, mindset, and artistry to show you exactly how to practice for confident, consistent performances—on stage, in the studio, and at the stand. Join the waitlist here →

✉️ 4. Stay in the loop (and in the practice room).

Not ready for a full commitment yet? Get weekly practice tips, mindset tools, and behind-the-scenes stories straight to your inbox—plus first dibs on new offers. Join the newsletter →

You deserve to have a musical toolkit that allows you to thrive. I combine my expertise as a professional flutist and software developer to give you a methodical, science-backed approach to learning even the most difficult music efficiently and effectively.

I combine it with elements of the Alexander Technique and the art of musical storytelling and interpretation to help you eliminate anxiety and perform effortlessly and with ease. Your playing matters—you have something to say, and I'm here to help you say it.

featured

Feeling inspired to practice this summer but not sure what you should be doing? I’ve totally been there before. 🙌 When I was a college student, my teacher would send me on my way at the end of each year with my new recital repertoire in hand. It was exciting, but it was also somewhat […]

GETthe COMPLETE STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE to FLUTE VIBRATO

If you're ready to achieve a natural-sounding vibrato, this is the guide for you—featuring a 5-step tutorial walking you through learning flute vibrato from scratch.

Inside you'll learn:

- How find the reaction in your sound.

- How vibrato is produced in the body.

- Why you need a flexible vibrato.

- What types of vibrato to use in your repertoire.

- How to practice vibrato.

YES, I'll TAKE THAT DOWNLOAD

hot off the digital shelf

GETthe COMPLETE STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE to FLUTE VIBRATO

MORE TO EXPLORE

My 5 Favorite Venues in Southern Tennessee

Read on the Blog

You Don't Need *This* $$$ Wedding Vendor

Read on the Blog

Let’s fix what’s not working—so you can get back to playing, teaching, and creating with confidence.

learn about flute lessons

explore coaching options

get help with your tech stack

© Sarah Weisbrod 2026. All rights reserved.

Legal | Site Credit | Photography by AMG Photography